di Marie Kortam [*]

Demographic pressure and the absence of the rule of law in Palestinian camps exacerbate the related problems of unemployment, poverty and, consequently, lack of prospects. This combination of factors leads to political and social instability as well as turmoil in the political, economic, and social systems. This also exacerbates existing violent conflicts, political violence and radicalisation. Such a scenario is increasing as young people have access to new communication technologies that show them the political and economic realities of other countries.

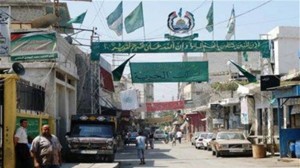

Ein El-Helwe camp (EEH) is the largest camp in Lebanon, with a population of roughly 120,00 residents between Palestinian refugees and other nationalities. Since the early 1990s, EEH has been a hotbed for Palestinian and Islamist political animosity. This situation has developed into armed conflict and violence between several Lebanese, Palestinian, Islamist, and regional forces, making EEH the most dangerous camp for the Lebanese army. For that reason, the Lebanese forces have tightened a siege on the camp, and in 2016 started to build a separation wall around its periphery.

These clashes and political conflicts led to the deterioration of the security-political situation in the “Palestinian diaspora capital” – the EEH camp. Today the camp is considered as an explosive security hub that can go off at any time during volatile local and regional political strife.

In this context, I seek to study radicalisation push and pull factors in EEH camp. Radicalisation is understood as an escalation process leading to violence. There are many paths to radicalisation that do not involve ideology. Ideology, violence and uniformity are the main distinguishing characteristics between radicalisation and extremism (Schmid: 2011; Mc Cauley, Moskalenko: 2011). Radicalisation can lead to violent extremism, which could be qualified by terrorist acts. Violent extremism emerges to replace the contentious nature of the term “terrorism”. The failure to find a consensus definition for terrorism has been political. Terrorism is a word of condemnation reserved for actions that are considered illegitimate and morally reprehensible and differs from government to another.

The reason to join radicalised or extremist groups cannot be limited or unique: «Individuals join as a result of perceived injustice and a need for some form of political activism. They join to meet sociocultural needs and the desire for social bonding stemming from identity issues. They are looking for meaning, which these groups provide in the form of ideology and higher narrative. There are also those who join for personal advantage, which might include access to criminal networks to enhance income, thrill seeking those looking for excitement, or redemption for those wanting to atone for previous misdemeanours» (ISD, 2012).

There are many models depicting the process of radicalisation. Common to several such models is the phenomenon of (perceived) relative deprivation, the search for identity, and sometimes also the assumed presence of certain personality traits in radicalised individuals. One of the first models was developed by Randy Borum in 2003. It lists four steps of radicalisation to terrorism:

1. Recognition by the pre-radicalised individual or group that an event or condition is wrong (“It’s not right”);

2. This is followed with a framing of the event or condition as selectively unjust (“It’s not fair”);

3. The third step occurs when others are held responsible for the perceived injustice (“It’s your fault”);

4. The final step involves the demonisation of the “other” (“You’re evil”).

Another model is the staircase model developed by Fathali M. Assaf Moghadam in 2009 for Islamic communities in both Western and non-Western societies. He uses the metaphor of a narrowing staircase leading step-by-step to the top of a building, having a ground floor and five higher floors to represent each phase in the radicalisation process that, at the top floor, ends in an act of terrorism.

At the end, authors agree that there be no single cause but a complex mix of that can lead to radicalisation and violence. To understand the radicalisation process in EEH, we thought on three levels: macro, micro-social (meso-), and micro-individual level.

Field Work and Research Methodology

This study covered political, security, social and individual relationships in the context of Palestinian-Palestinian interactions and emerging Palestinian-Lebanese issues. The aim was to connect these elements in a logical framework to understand the radicalisation and violent extremism process of some Palestinians along with the existing frameworks and forms for countering violent extremism or preventing it.

The study followed a qualitative methodology based on the socio-political context of EEH, the roots of radicalisation, the perceptions of stakeholders regarding the social, political or security matters along with the temptations to stop the process of radicalisation to violent extremism or to prevent radicalisation.

The main approach to this in-depth research was to carry out extensive interviews with four types of stakeholders during 2017. These interviews involved 37 individuals, representing 29 associations, international foundations, unions, movements, factions, Lebanese and Palestinian security forces and personalities, including six women. The interviewees were selected on the basis of their location and their role in violent extremism, countering it or prevent it, on their status and position in society and their relation to the subject of the study.

I- From radicalisation to violent extremism

Environment represents the ground floor, in the Moghadam’s model (2009), where Palestinian refugees stand for a cognitive analysis of their structural circumstances. In this context, Palestinian refugees feel that they are not treated fairly and interpret their situation as structurally unjust.

EEH’s population and its surrounding neighbourhoods are estimated to be between 105,000 [1] to 120,000 [2], while it is estimated to 69, 522 in the last census of the Palestinian-Lebanese Dialogue Committee including 59,201 Palestinian refugees from Lebanon. These figures take into account the geographic expansion of the camp due to the increasing number of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon and those displaced from other nationalities. Despite the varying figures, EEH remains without any doubt one of the largest Palestinian camps in Lebanon.

Nevertheless, this huge number of refugees is not the main reason leading the Lebanese Government to deal with EEH through a primarily security approach. This camp represents openly Islamist elements from the movement linked to foreign Islamists, including Daesh, after the eruption of the Syrian crisis. The crisis in Syria has become the focus of some jihadist and Salafist jihadist groups, such as Al Shabab Al-Muslim, Fatah Al-Islam, Jund Al-Sham, Al-Maqdisi group [3] and Abdullah Azzam Brigades. These groups, which are hostile to the Lebanese Army and Hezbollah, have a close political relationship with some of the Syrian opposition factions, especially Al-Nosra Front and Daesh according to Pouillard (2015). However, before the war in Syria took place, the EEH witnessed numerous bloody clashes between armed factions, bombings, and assassination attempts, related to a constant search for a balance of power, territorial control, and tribal revenge.

As is the case with other Palestinian camps in Lebanon, residents of the EEH camp live in very difficult circumstances amid precarious economic and health conditions, which cause diseases, health problems due to the close proximity of buildings. It is the only camp that has fixed barriers and control towers at all entrances under the surveillance of the Lebanese Army. Soldiers check identity papers, vehicle papers and register all entries and exits. Each checkpoint has an iron gate that allows authorised cars to pass, one by one. This is in addition to the separation wall that surrounds the EEH camp, with a height of six metres and control towers distributed along the wall with a height up to nine metres according to the military plan. The construction of this wall was supposed to start in 2012, but the implementation was delayed until September 2016, for securing the funds [4]. The main reasons for such tight and stringent security procedures, concerning the wall, are maintaining security inside and outside the camp, controlling entry and exit and restricting the entry of weapons and other prohibited items. Dozens of factions share the security and political control of the EEH camp.

The EEH camp has five entrances for vehicles. The two northern entrances are the Saida Government Hospital and Al-Taamir. Al-Nabaa is the entrance from the east. As for the southern side, the entrance is by Darb Al-Sim located in the neighbourhood of Loubie and Hittin, with a remarkable presence of Salafist and Islamists groups. The west part of EEH starts from the northern side in the Al-Sekke District, to the Nemreen neighbourhood, the entrance is by Al-Hesbe in the west centre, where there is a presence for the PLO, Usbat Al-Ansar and the Joint Force.

Meso level: violent extremism and radical milieu [5]

At first sight, the EEH appears to be a besieged area bordered by checkpoints set up by the Lebanese Army at the camp’s entrances and perimeters. When talking to camp residents, the most difficult question seems to be: How is the situation today in the EEH? The answers change with time, place and people with different political opinions. However, the commonly agreed upon and prominent view in each answer is that it is “difficult to describe”. Those individuals are dissatisfied from the situation in the ground floor and move up to the first floor (Moghadam, 2009) in the search for a change in their situation by an engagement in politics or civil initiatives. They passed to the first floor, and are actively seeking to remedy those circumstances they perceive to be unjust. They have a mitigated opinion and try to deal with the situation.

However, this tense and volatile situation leads to internal conflicts in Palestinian society, ranging from simple disputes to armed clashes conflicts. Despite its diversity and multiple forms, the conflict in the EEH camp appears to be deep-rooted due to the overcrowded conditions in the camp, drug addiction and abuse, family disintegration, family disputes continued economic marginalisation, denial of human rights and the practice of subtle legal forms of discrimination by the Lebanese authorities, and repression by the Lebanese security, such as the wall, malicious denunciations, revenge and assassinations.

Representatives of the Palestinian factions link the situation in EEH camp to the regional and local Lebanese political situation. Those representatives confirmed the existence of groups that do not belong to the social and political fabric of the camp. These groups have extraneous connections and agendas. All factions have denied their own responsibility for what is happening in the camp and claimed that they were defending themselves, and not their influences or control, in the face of hidden hands that were trying to make a similar scenario to that of Nahr Al-Bared [6]. What happened in the Nahr Al-Bared camp terrified stakeholders in EEH, leading them to stand up against such image showing the camp as a hub for exporting fundamentalist groups or spreading fundamentalism, in the hope of sparing the EEH camp any attacks, similar to what happened in Nahr Al-Bared camp.

According to Moghaddam (2009), some individuals might find that paths to individual upward social mobility are blocked, that their voices of protest are silenced and that there is no access to participation in decision-making. They tend to move up to the second floor, where these individuals are directed toward external targets for displacement of aggression. They begin to place blame for injustice on in- and out-groups such as the Fatah Movement, the Lebanese State.

Since Usbat Al-Ansar (Kortam,2021), the first armed jihadist group, in neighbourhoods considered “exiled”, as EEH camp young people establish identities under the logic of stigmatisation and learn to see themselves as devalued. Some react by attempting to find a context in which they may strongly affirm themselves as a “we” and consider violence an adequate form of self-expression.

Terrorist or criminal networks attract youth easily because they listen to their needs and demands, show that they understand them better and appreciate their spirit of rebellion and their perception of justice. The leaders of “imagined community” (Bonelli, Carrie, 2018 :213) know the right time to approach the vulnerable youth to transform their defeat and frustration to a virtuous choice by offering them a way of salvation. This relation of “bonding” and “bridging” (Putnam, 2000) and find among them protective sociability (Bonelli, Carrie: 2018).

In this violent environment two grievances play an important role as mobilisation than as a personal experience: The file of the wanted individuals by the Lebanese authorities and the separation wall.

Real and perceived grievances

A sense of injustice is a very powerful motivating factor that can make individuals join armed groups. Grievances alone cannot explain violent radicalisation. The cognitive environment explained before offered triggers events to link grievances to an internal and external enemy who is held responsible for them or who is deemed to stand in the way of removing causes of grievances.

The File of the Wanted Individuals by the Lebanese Authorities

Related to multiple clashes in EEH in 2017, there was a Palestinian-Lebanese meeting, called upon by MP Bahia Hariri in late August 2017 in Majdelyoun [7], in which the PLO factions, Coalition factions and Islamist Forces were present. The participants in the meeting issued: 1) a collective statement calling for the end of clashes in the EEH camp; 2) a call for the Palestinian political leadership to meet in the Palestinian embassy in Beirut. The meeting in the embassy was attended by PLO factions, coalition and Islamist Forces and Ansar Allah. A roadmap and recommendations were released forming three committees: a Follow-up Committee for those wanted by the Lebanese authorities, a Coordination Committee in Saida and an Operational committee to follow up the consequences of the EEH clashes [8].

The Wanted Individuals Follow-up Committee consisted of eight members from the four political parties in the camp: one representative of the Islamist forces, Sheikh Jamal Khattab, one representative of Ansar Allah, Mahmoud Hamad, the Deputy General Secretary, three representatives of the coalition, Shakib Al-Ayna, Jihad Relations’ Officer, Ghazi Dabour, the leader of PFLP-General Command, Shouhdi, the leader of Al-Nidal Front, three PLO representatives, Ghassan Ayoub from People’s Party, Hussein Fayyad, the Secretary of Fatah movement in Lebanon, and Salah Al-Yousef, head of the Palestinian Liberation Front in Lebanon.

The Separation Wall

The separation wall goes along the Saida highway and encircles houses from the army position at Saraya Roundabout, along the neighbourhoods of Al-Sekka, Al-Joura Al-Hamra, Abu Jihad Al-Wazir playground, Al-Zib, Al-Ghweir, Hittin, Darb Al-Sim. Its length exceeds two kilometres.

The wall penetrates deep into the ground to prevent the digging of tunnels for infiltrating the camp from underneath it. According to official Palestinian source [9], the first phase of the project includes the construction of the wall on the southern highway – Saida from Darb Al-Sim to Saraya Roundabout, which may take several months, but talks are being held between the Palestinian forces about completing the ring around the whole camp in the second stage.

Residents compare EEH wall with the Separation Wall in the West Bank. None of the dwellers accepted the wall and they were supported by Lebanese stakeholders. Lebanese politicians issued a statement rejecting the wall that adds to the misery caused by the Israeli [the Nakba]. The most prominent signatories opposing the wall were Bahia Al-Hariri, Ousama Saad and Fouad Siniora. Palestinian political leaders condemned the wall, but conceded that they had no choice in the matter while commenting: «The state will build it. We can do nothing. We will not enter into a battle against the army»[10]. Sheikh Maher Hammoud said: «the situation is irregular, military sources said that if Saida was secured, the camp will be secured, they will proceed and no one will object. We weighed the cons and the pros and we chose the positive effects. The wall will not prevent some people in Saida from reaching their groves»[11].

The Lebanese army sources [12] stressed that the wall will not prevent the exit and entry of those wanted people, but it will limit the entry of explosives. They noticed that seventy percent of the explosives and explosions in Lebanon came out from EEH and Arsal. Since the construction of the wall and the battle of Fajr Al-Jouroud, bombings stopped in Lebanon. Also, to assert a tight control over the mobility of individuals, the Lebanese army cooperated with the Ministry of Interior to replace the Palestinian paper identity cards with biometric cards.

This second part represents the wider radical milieu – the supportive or even complicit social surround – which serves as a rallying point and is the “missing link” with the terrorists’ broader constituency or reference group that is aggrieved and suffering injustices which, in turn, can radicalise parts of a youth cohort and lead to the formation of terrorist organisations.

Micro level: different paths of radicalisation

In EEH two paths of violent radicalisation can be observed: ideological path and criminal path. Violent radicalisation is related to the overall political, socio-economic and security situation such as wanted individuals, “terrorists”, weapons proliferation, Lebanese Army barriers, the wall and the effects of the armed clashes. Disenfranchised youths are suffering from identity problems, failed integration, feelings of alienation, marginalisation, discrimination, relative deprivation, humiliation (direct or by proxy), stigmatisation and rejection, often combined with moral outrage and feelings of (vicarious) revenge. They formed an Islamist network call by media Al-Shabab Al-Muslim (Muslim Youth), some of them are radicalised ideologically and others become under this network for protection after a crime or security problems. The most famous case is Bilal Bader who becomes a hero after being a criminal. First of all, who are “Al-Shabab Al-Muslim”.

“Jihadist Islamist Actors” or “Al-Shabab Al-Muslim”

Identified by the media as Al-Shabab Al-Muslim, they represented an informal network of individuals to describe extremist individuals belonging to this jihadist network [13]. They brought together young people from Fatah Al-Islam to Jund Al-Sham in the EEH camp and participated in violent clashes with Fatah. Al-Shabab Al-Muslim leaders do not go outside their controlled quarters in the camp.

Al-Shabab Al-Muslim included individuals who have been neglected by several parties and organisations. They received a religious education by many clerics in several movements, the most notable of them is Usbat Al-Ansar, which absorbed many young people who refused and challenged the various Palestinian parties and Lebanese authorities.

Rami Ward [14] said: «Usbat Al-Ansar was mobilising us against the Lebanese Government by teaching ideas and concepts for fighting the state and its institutions. Now, we carry forward this opposition to the state, although Usbat Al-Ansar is no longer against the state» [15]. Rami Ward was a former member of Usbat Al-Ansar, and a prominent Islamist figure in the EEH camp. He is the son of a Fatah commander and several warrants for his arrest were issued in the past twenty years. With the decline of the Palestinian revolution after Oslo and the Iraq war, Rami was among many young men who joined Usbat Al-Ansar. He left Usbat Al-Ansar after 8 years, when the armed group sign a cease-fire treat with Fatah. Today, after many years of membership in Usbat Al-Ansar, Rami says: «In retrospect, I think, Usbat Al-Ansar was correct in not fighting the state, but at the time, we were young and energetic».

Those who are affiliated to Al-Shabab Al-Muslim, rejected this label because they considered everyone in the camp as a Muslim, by religion. Raed Abdo or Abu Omar was the Islamists leader in Hittin quarters. He was aware that they have inherited tribal conflicts with an Islamic character and in such type of conflicts there were no winners on the long run because of internal clashes: «The problem between factions in the camp started as a fight for power between Amin Kayed (Fatah) and Hisham Shridi (Usbat Al-Ansar) in Al-Safsaf quarter, but has now been carried forth by the second generation while being more characterised as dispute between Islamists and nationalists» [16]. The tribal structure of Palestinian society upheld the clan over the organisation. Abu Omar’s approach was to support the oppressed. He stressed that a terrorist was “created” by society and gave the example of Bilal Badr’s last battle in August 2017, in which he was deemed a terrorist for defending himself. This explains the existence of members in Al-Shabab Al-Mulsim with varying degrees of consciousness about their Islamic duty. Abu Omar explained, «were exception cases such as young men who claimed to belong to Al-Shabab Al-Muslim in order to carry arms». What happened recently with Mohamad Hamad, the son of Sheikh Jamal Hamad was a main example of this.

There was no doubt that young people who carried forward the ideas of Daesh, or Islamic state, and Al-Qaeda did exist in the camps. Such as Imad Yassin case, who was one of those youngsters belonging to the Islamic State, as announced by the Lebanese Army, who arrested him in September 2016 [17].

Criminal Path

A we said before many of youth belongs to the “imaginary community” of so-called Al-Shabab Al-Muslim is because of protection. I take the example of Bilal Badr and then I will develop the idea of misguided youth.

Bilal Badr “ The Hero of the Camp”: protection belonging to Al-Shabab Al-Muslim

During an interview with Al-Shabab Al-Muslim, Muslim youth leaders, in the EEH camp, one recounts the story of Bilal Badr, a 27-year-old Palestinian youth close to Fatah Al-Islam and Al-Shabab Al-Muslim. Badr became the most wanted person, by both the Palestinian and Lebanese authorities. «He was another young Palestinian, like the rest of the youth, who spent all his time in the streets and was just a qabaday, but not an Islamist. One day a Fatah member killed [Bilal’s] best friend in front of his eyes. In response, Bilal shot a Fatah member, wounding his thigh. Fatah forces inside the camp started hunting Badr, who took refuge in the Islamists’ quarter for protection and to avoid custody or arrest; and hence he became closer to Fatah Al-Islam Organisation» [18].

In his last battle, Bilal Badr issued a statement announcing his withdrawal from the Al-Tireh Quarter in order to prevent the neighbourhood from being destroyed. Badr’s withdrawal came out after the intervention of wise respectful mediators, as Sheikh Ousama Al-Shihabi described them (see below): «The wise people intervened to solve the problem, but without a radical solution [to the conflict between Islamists and Fatah]». Due to this, on 26 August 2017, Al-Shabab Al-Muslim issued a statement to denounce what happened. Here is an extract from the statement: «What happened in EEH camp a few days ago was a disgrace, but it draws attention to the international community’s unjust treatment of this camp, where more than 100,000 people live. This criminal system (international community) is the one who conspired against Palestine and its people and abandoned them. This criminal system decided to destroy and displace the people of the camp under the pretext of terrorism and we cannot accept these serious allegations against our camp. We as Al-Shabab Al-Muslim, were still keen not to shoot one shot in the camp and keenly understand politics. Having felt there was a danger looming around the camp, we took practical steps to exit our beloved camp in the aim of sparing our people the dangers, instead of humiliating them».

On January 2, 2018, Bilal Badr announced his departure from EEH camp, and went to Idlib to join the Islamist state [19]. He is back on September 2018. Two relevant factors appear to explain why youths are radicalised and engaging in fights. The first one is giving by Sheikh Jamal Hamad, a leader of Al-Shabab Al-Muslim in the EEH camp, highlighted another factor in understanding the dynamics of extremism. For him, the spontaneous and volatile youths in the refugee camps are sometimes uncontrollable, even by the Islamist and religious leaders themselves. He explained that the military clashes between Fatah and Bilal Badr in early April 2017, can only be explained by moral and ethical factors, by defending their honours and women, in addition to ideological and political factors. He said: «Many Palestinian Youths in Al-Tireh quarter who are not affiliated to Islamist organisations stood up to fight with Bilal Badr and took up arms because they felt insulted by threats made by Fatah on social media, including [we will rape your women]. Fatah leaders did not apologise to ease the tension»[20]. The second one is based on some NGO activists statements in the camp, for them the rise of the jihadist movements is due to the lack of a nationalist culture among the young people.

The case of Bilal Badr is like that of many young men in the camp suffering from marginalisation with no real prospects. A study by the Norwegian People’s Aid organisation on the exploitation and marginalisation of young Palestinians (Kortam, Dot-Pouillard, 2017), concluded that the Palestinian youths have no choice but to emigrate, or take drugs, or to adopt religious/political extremism to escape from their awful reality. These young people live on the margin – unemployed, poor and deprived – without any future personal plans or collective projects helping them to embrace their desires. Some, like Bilal Badr, adopted Islamist objectives to establish an Islamic Caliphate, which they considered as the first and only project that they were able to choose, which will provide them with an outlet for self-realisation. They perceived this objective as being in accordance with their beliefs while giving them the opportunity to express and translate their anger against the injustice they faced on a daily basis. They became jihadists for the sake of Allah under the banner of Islam; regardless of its positive or negative nature, they turned visible to the community and other groups. They moved from the shadow to the light and became both known and wanted for aligning with a project that gives them a place in society.

Useless Youths-Misguided Youths

This issue is very complex. The young Palestinians were searching for the meaning of their existence within frames or references through which they can build a collective identity and set common goals. Those youths found the solution in emigration, joining a military party, adopting religious extremism, or taking drugs, as shown in the recent study conducted by the Norwegian People’s Aid (Kortam, Dot-Pouillard, 2017). Many examples were illustrative of this model; we chose here to put forward the recent conflict in EEH camp, which highlights the pace and tempo in what we call the youths’ swing between social deviation and extremism.

What happened recently with Muhammad Hamad, son of Sheikh Jamal Hamad, a leader of the Muslim Youth group, is an evidence. Mohammed Hamad, 18, was injured during the April 2017 armed clashes between Bilal Badr group and the factions in EEH camp. He was wounded in the head and treated in the public hospital located on the entrance of the camp. Upon his discharge from hospital, he managed to reach Syria and joined the ranks of Daesh. He returned to the camp a few months later.

In a field visit to Jamal Hamad at his home on 16 October 2017, he confirmed that Mohammed went to Syria and returned from there. After we insisted to meet him, Mohammed appeared frantic and angry; he swiftly rushed back to his room. Because of his father’s status, Muhammad is considered as a member of the Al-Shabab Al-Muslim but he can be placed more in the category of reckless young people, whom Abu Omar from Hittin quarter described. In addition to the extremist religious and partisan ideas spread among the youths, recklessness and weapons, can be considered as a combination that facilitates the slide into armed violence.

Mohammed Hamad is one of those young people living amid such circumstances. On January 24, 2018 [21], Al-Shabab Al-Muslim issued a statement denouncing Mohammed Hamad’s behaviour by repeatedly harassing a girl in the street and using his weapon to defend himself when he was deterred by passers-by. The statement also condemned Sheikh Jamal Hamad’s reaction to his son’s defence. Since then, there have been negotiations to deliver Mohammed Hamad to the Lebanese army since he is one of those wanted by the state.

The political leader of the Hamas movement in Lebanon, Ahmed Abdel Hadi, and the head of the World Union of Resistance Scholars, Sheikh Maher Hamoud, have played a prominent role in persuading and facilitating the extradition of Mohammed Hamad to the Lebanese army intelligence in the hope of closing this issue. The extradition was scheduled before the last clash.

Few days later, Mohammed Hamad caused again violent clashes in the camp for two days. On February 9, 2018, Ayman al-Iraqi, a member of the National Security Command in the camp, intercepted Mohammed Hamad near the vegetable market while distributing water. Ayman al-Iraqi fired at Mohammed Hamad in order to arrest him, the latter responded by shooting back, and clashes spread in the camp. The situation was aggrandised more by the killing of Abdul Rahim al-Maqdah, son of Bassam al-Maqdah the media official of Al-Haraka Al-Islamiyya Al-Mujahida, and the grandson of the secretary of the Popular Committee of the coalition forces and the head of al-Sa’ka organisation.

This incident provoked reactions from Islamist leaders, calling for united efforts to put an end to the chaos of weapons. Sheikh Jamal Khattab the head of Al-Haraka Al-Islamiyya Al-Mujahida, and notably the secretary general of the Islamist Forces, called for an end to the series of clashes in the camp, along with controlling the spread of weapons. He also stressed the need for activating joint action, unifying the Palestinian political leadership in Lebanon, and discussing the role of the joint force. The second reaction comes from the spokesman of the Islamist Usbat Al-Ansar, Sheikh Abu Sharif Aql, who considered that the camp is in immense need for cooperation between its factions in order to address all the prevailing security, social, and living problems. In addition to that, the Secretary of the Popular Committee of the Palestinian Coalition Forces, Abd Makdah, grandfather of the deceased, called to put an end to the chaos of weapon spreading in the camp, while stressing the need to exert every possible effort to maintain security and stability.

The incident sparked a new speech as the aggressors and the victim belonged to Islamist forces. Sheikh Jamal Hamad, a symbol of Al-Shabab Al-Muslim found himself in a hard and embarrassing situation inside the camp. He was asked by different factions to extradite his son to the Lebanese authorities. Finally, he conceded and extradited his son on February 12, 2018. In return, Fatah delivered, Ayman al-Iraqi, the member of the national security that shot Hamad.

Strategy of countering and preventing violent extremism

Countering radicalisation is understood as any effort to counter radicalisation that lead to terrorism. In this regard, many initiatives have been taken by the various civil and political actors, individuals and institutions, whether official or unofficial, that are not traditionally associated with national security. These actors try to play a mediation role to assist individuals during a conflict to turning away from violent extremism or terrorism in the weakness of national security services. In the following, I will analyse the weaknesses of the three essential Palestinian security institutions within the camp and the Lebanese security institutions dealing with the camp, then the political, religious and civil initiatives to counter radicalisation.

Palestinian Security Institutions

Taking into account the security levels in the EEH, the National Security Forces and the Joint Force struggled to maintain security. The Legal Support Unit of the Palestinian National Security Forces in Lebanon was also established to help the security forces realise their role as the community police and to aid them in the proper use of their weapons.

The most prominent Lebanese security institutions in the EEH camp which can serve as intermediaries to calm down the warring factions in any escalator situation are the Directorate of General Security and the Directorate of Intelligence in the Lebanese Army.

a- National Security Forces

General Commander Major of the Palestinian National Security Forces, Subhi Abu Arab described the situation in the EEH as good. He claimed that the forces are in a constant confrontation with terrorists and classified every person resorting to vandalism as a terrorist. The armed forces are obliged to act according to the decisions of the political leadership in the Palestinian Embassy in Beirut and the statements of the Joint Force. However, this apparatus suffered from several weak points and internal problems until clashes were sparked between the forces of the deputy commander of the Palestinian National Security Forces in Lebanon (Brigadier Munir Al-Muqdah) and the forces of the commander of Saida and the south in the Palestinian National Security Forces (Brigadier Muhammad Al-Armushi). On November 26, 2017, the groups of each official engaged in armed confrontations in the EEH. The dispute broke out after a period of internal disputes between Maqdah and Al-Armushi on the issue of succession of the National Security Chief. Maqdah is the deputy of Abu Arab and Al-Armushi is supported by the Director of the Palestinian Intelligence, Major General Majid Faraj; he also led the second battle against Bilal Badr in the Al-Tireh quarter [22]. The question that remains unanswered is how a security organisation that undermines the security of the camp, can maintain its protection at the same time?!

b- From the Palestinian Security Forces to the Joint Force

The armed struggle unit, Al-Kifah Al-Musallah, was a Palestinian militia that played the role of the police in the camps and the security committees did their best to maintain the security of the camps while the popular committees took over the social issues and tasks. The Palestinian Security Forces under the authority of PNSF replaced on the ground the armed struggle groups in the EEH. The armed struggle was headed by Mahmud Abd Al-Hamid Issa -Al-Lino – from 2008 to 2010. Relations between the latter and Munir Al-Maqdah were rather tense until 2012, due to a struggle to take the head position of the Palestinian Security Forces. Al-Lino was close to the former leader in charge of the Palestinian Security Forces in the Palestinian territories, Mohamad Dahlan, who was ousted from Fatah in July 2011.

In 2013, Al-Lino launched the reformist movement in Fatah in Lebanon with the support of Mohammed Dahlan and was dismissed from Fatah. The Palestinian political leadership initiated the establishment of the Supreme Security Committee composed of all factions including nationalist forces, Islamist forces and Ansar Allah. This committee was charged with coordinating the Palestinian security policy in all camps under the leadership of Major General Subhi Abu Arab. It is the ultimate security reference for the Palestinian camps, after the unified political leadership.

The Palestinian Security Forces were established in all camps to negotiate with the Lebanese army on issues relating to the security situation prevailing in the camps. The Security Committee officially appointed Maj. Gen. Munir Al-Muqdah as its president in February 2015 and the Palestinian Security Forces were deployed in the EEH camp and Miyeh & Miyeh, in winter 2015, then in Borj Al-Barajneh camp in Beirut, in June 2015, and will be deployed later in the remaining Palestinian camps.

In February 2017, Fatah decided to suspend its participation in the Higher Palestinian Security Committee in Lebanon due to a large number of unresolved differences between Fatah movement, factions of the PLO and the coalition of the Palestinian forces on a variety of arrangements and jurisdictions. This meant that the political cover was automatically withdrawn from the Palestinian Security Forces. Its leader in Lebanon was forced to resign later while remaining subjected to the authority of Fatah movement in Lebanon [23].

Palestinian Nationalist and Islamist forces in Lebanon agreed to dissolve the Palestinian Security Forces in the Palestinian camps on 4 March 2017, after the Supreme Security Committee was dissolved. They agreed to form a new force only in the EEH camp under the name of the “Joint Force” led by Fatah leader Bassam Al-Saad, to maintain security and stability in the EEH camp.

This agreement came after the visit made by the Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, Abu Mazen, to the Lebanese prime minister, Saed Hariri. After this visit, the joint political leadership in Lebanon held a meeting in the Palestinian embassy in Beirut, with the participation of Palestinian Ambassador Ashraf Dabour. The meeting concluded the establishment of Joint Force composed of 100 officers as following: 60 members of Fatah movement and other PLO member factions, 40 members from the coalition factions, Islamist forces and Ansar Allah. This Joint Force has to maintain security and stability in the EEH camp.

In the wake of the recent clashes, the new Joint Force was given wide powers to intervene immediately when necessary, without having to return to the political authorities for instructions. The Joint Force work under the slogan of «force, unions, solidarity, unity, security, stability and consensus», as Colonel Bassam Al-Saad [24], former head of the Joint Force. explained in an interview:

Since the Joint Force look forward for reconciliation and dismantling the various security squares, they proposed a forthcoming meeting with all the Neighborhood Committees and the Popular Committees to coordinate the extradition of wanted persons, while restoring the close family ties in the camp, like before.

Lebanese Security Institutions

a- Director General of Public Security, Major General Abbas Ibrahim

The Lebanese authorities involved in the security dialogue with the Palestinians, include the Minister of Interior and Municipalities, Nuhad Al-Mashnouk, a member of the Future Movement headed by Saad Hariri, the General Directorate of General Security under the chairmanship of Major General Abbas Ibrahim, who has been the special interlocutor since 2012 when the file of Palestinian refugees was given to the General Directorate of General Security. Azzam Al-Ahmad, member of the revolutionary council at PLO and the responsible of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, met Major General Abbas Ibrahim during his visits to Lebanon, knowing that Abbas Ibrahim was a key interlocutor of the Palestinians. He was the representative of the Army intelligence in the South between 2005 and 2008. This role made him close to the camp, its factions and the officials who received him from time to time to review the situation in the camp. In December 2015, a delegation from the Arab Zbeid Association, including the head of the Arab Zbeid Committee, a member of the Ousama Al-Shehabi family (see above) visited him at his office in Beirut.

In March 2016, he also hosted a joint meeting at the United Nations headquarters in Beirut, inviting the political leadership of the Palestinian forces, various factions, the General Director of UNRWA, and the United Nations representative in Lebanon, in order to discuss ways of dealing with the conflicts taking place between the two parties, particularly after UNRWA’s decision to cut services amid Palestinian protests rejecting the decision.

He played a large role in the settlement of the file related to the wanted individuals by the state [25], in coordination with all the security services.

b- Lebanese Army Intelligence

The Lebanese army is responsible for the security of the camps, especially the Intelligence Directorate in Southern Lebanon, which plays a central role under the command of Brigadier General Fawzi Hamadeh, who succeeded Brig. Gen. Khoder Hammoud on April 18, 2017. Brigadier Hamadeh holds regular meetings with the Palestinian National and Islamist Forces leadership, without forgetting an unwritten clause in the Cairo Agreement (1969) regarding assigning responsibility of the security of the camps to the Palestinians exclusively and prohibiting the entry of the Lebanese army to the camps. Although this agreement was rescinded by the Lebanese Parliament on 21 May 1987, its implications are still implicit in all camps, except for Nahr el-Bared after its destruction. In general, the army’s role is limited to controlling entrances to the camps, setting up checkpoints and administering the permits’ system [26].

In addition to the security actors, non-security actors play a role in countering radicalisation in EEH camp, such as local political leaders and religious figures. Sheikh Maher Hammoud [27], the Imam of the Jerusalem mosque in Saida, who exerts great efforts to reduce tensions between some Salafist Islamist groups and Hizbollah. Within the political level, there is the leader of the Nasserite Popular Organization, the former MP Ousama Saad [28], the former mayor of Saida, Abdel Rahman Al-Bizri, and the MP Bahia Al-Hariri [29]. In the third level, counter radicalisation is aimed by the Palestinian civic and popular initiatives inside the camp, such as the Neighborhood Committees.

a- Neighbourhood Hittin Committee

Neighbourhood Committees can play an important role in the camp. Most notably, the Hittin Committee, which includes locals living in Hittin. The Committee is concerned with general problems and was established in 2004 after the clashes that took place between Jund Al-Sham and Fatah [30]. Activists from the Hittin neighbourhood attempt to prevent tensions in the Hittin area. Hajj Ali Aslan [31], the head of the Administrative Committee, who has been attending the Committee meetings since 2011, said: «the Committee is composed of seniors from all the families, with the participation of young people who meet on a weekly basis and discuss social problems to be resolved, such as murder, imprisonment, tribal reconciliation and payment of dues. The Committee protects the quarter from ongoing problems with Fatah and others» [32]. Such committee system was developed in 2011. Before that, the committees were not very functional due to the death of some elderly people and the failure of others. The reactivation of the Committee was discussed with Mansour Azzam, the owner of the Azzam complex in EEH (see above). The Committee was headed by the latter. Usually an Administrative Committee includes the Director of the Administrative Board, a Secretary, a Treasurer, a Financial Officer, an Education Officer, an Infrastructure Officer, a Social Affairs Officer, a Public Relations Officer, and an Advisor to the Hittin Committee. The Neighborhood Committees work for the public interest, regardless of political, familial or tribal affiliations of each member. The engagement with the committee is a priority that precedes all affiliations. Each family has its representative in the Neighborhood Committee and each family has the right to choose whether or not to join the Neighborhood Committee. There are 32 members of the Hittin Committee, while the Administrative Committee consists of 10 elected members, who are changed annually.

The Committee has a social role to play based on communication, mutual trust and credibility in family “mediation”, to maintain security in the region, but without interfering between the factions. Hajj Ali said: «The basis of the relationship with the people is confidence once confidence is established, you become a decision maker and influential. So control becomes affection, love and charisma, not power». The Committee proved its effectiveness in 2014 during the battle between Al-Armushi, the PNSF National Security Chief in Saida and Al-Shabab Al-Muslim. The Committee succeeded in exerting pressure to prevent fighters on both sides from entering the neighbourhood, but the battle soon spread to other neighbourhoods.

As Hajj Ali is a member of Hizb Al-Tahrir, he has political and religious knowledge and this makes the Committee more effective and far-reaching. He is the principal interlocutor with the armed Islamists. His dialogue sessions with some of these groups produced a remarkable development and an important change in the convictions of Islamists along with their approach to conflicts in the camp. In the past, they believed that fighting in the camp destroyed buildings and infrastructure, but now they realise that there are also social and psychological effects for clashes. Also, as Islamists, they felt that they have the right to fight Lebanese soldiers or Fatah fighters, since they are secular and it is permissible to kill them, and if Islamists were killed during such clashes than they are martyrs. So during dialogue sessions, such issues were discussed from a religious point of view, and it was shown that it is religiously permissible for a soldier to defend his homeland, as well as issues relating to the prioritisation of interests.

b- Popular Initiative

Popular Initiative Al-Moubadara Al- Shaabiye was created in 2012 by a group of young activists motivated to face injustice in the camp as a result of continuing violence and insecurity. Young people were unified to form a force of pressure and influence on the leadership, parties and political forces. Popular Initiative played an important role in initiating dialogue and defusing tensions along with explosive situations. The Popular Initiative included 63 young people; the members were considered credible by all parties, even though some are fighters from different factions.

Every one of them considered preserving the camp unity and Palestinian national identity as a priority. Youths belonging to different political parties were members in the Popular Initiative. Some of them also played other roles. For example, Jihad Mawed is the President of the Popular Initiative and the president of Saffouri neighbourhood committee. He conducted conciliatory initiatives through these two roles.

During clashes, the Popular Initiative members endangered their lives and went to the streets conducting demonstrations and sit-ins. They commemorated national events and cooperated to face insecurity in the camp while coordinating with the Neighborhood Committees. Popular Initiative financed its activities from the monthly membership fund, where no activity exceeds ten dollars for funding.

The popular initiative is not limited to coordination only. They also meet with actors, civil society organisations and Lebanese political parties when necessary, aiming to exert pressure on the Palestinian political leadership.

Popular Initiative is part of Crisis Cell. This cell tried to prevent the reduction of the UNRWA’s[33] services. It exerted pressures, held several meetings and raised memos, because it considered the suffering of the refuges is not only rooted in security or political issues, but also in humanitarian and social issues. It organised a movement against the quotas in the reconstruction projects or rehabilitation of houses in UNRWA. The popular initiative coordinated with the Neighborhood Committees to study the conditions of the selected houses for rehabilitation. Sixty-four houses were found to be in a relatively better condition and thus were not covered by the project in its first phase. In addition to medical services, and in coordination with other actors within the Crisis Cell it played a role in reconciliations between the families of a murderer and the victim, to resolve the issue instead of resorting to the authorities. This Crisis Cell became active during a crisis and hence the conflict between the Popular Initiative, the factions and the forces lead to a form of a social pressure aiming to resolve conflicts peacefully. Their initiative faced many obstacles, but their determination was never affected by any obstacles.

However, the initiative is proud of its achievements, especially its role in determining the eligibility of houses for restoration, which was coordinated with UNRWA. Most importantly, the initiative has given the youth inside the camp the opportunity to present a critical alternative point of view. This last activity is as proof that popular action, if it is honest, can have a positive effect despite the fights, forces and the attempts by parties or factions to boycott its monthly meetings. Popular Initiative has evolved as a result of certain circumstances, namely, the explosive security situation. It might cease to exist when stability and peace are maintained.

c- The “I am a Mother, I Want to Protect my Son and my Daughter” Campaign

Fayza Al-Khatib [34] introduced herself as a Palestinian mother of five children, working as a kitchen supervisor at the Saida Women’s Cooperative. Fayza recounted her initiative in 2013, following the security tensions and the conflicts in the EEH camp. She asked every Palestinian mother to assume her individual responsibility as a mother and play a role in trying to reduce the clashes by influencing her sons, brothers, father or husband to avoid sectarian affiliations and carrying arms, in the hope of stopping the clashes.

In 2013, the situation was very bad, that at least a person was killed every week and this had a severe psychological impact on the camp population, especially young children. One night Fayza received a friend escaping the clashes near her home. They decided to organise a demonstration to express their dissatisfaction with the murderous fighting and senseless killing. They began to stroll the streets of the camp and called on the individuals from households one by one, to raise awareness amid the mothers about the impact of the clashes on their children and express the need for mobilising demonstrations during the night for such cause. Certainly, many residents told them that their efforts would not work. The demonstration began and upon their arrival in Al-Safsaf quarter, fighters shot at the demonstrators.

After this, they launched a campaign, «I am a Mother, I want to protect my son and my Daughter», about which they distributed flyers to all local families. They continued their efforts for three months, prepared posters protesting the conflict to distribute at each entrance of the camp. They protested even by lighting candles every night. The Palestinian Women’s Union sometimes joined them, but the pressure on the women in the campaign continued to grow through the Palestinian Women’s Union and the political factions via the husbands. The campaign, however, did not last long and was stopped.

From Intermediaries to Mediators

EEH camp has many problems at every level, from individual to social, while it is easy to stereotype these problems, which are not limited to Palestinian society alone. Such problems are found in several marginalised communities living in neglect similar to what is happening in EEH camp, whose refugees are waiting for return to their homeland. There are also advantages in this society, which were often highlighted. As in other refugee camps in Lebanon, due to the hard social and economic situations, the youths resort to radicalisation, drugs and migration. There are innumerable community initiatives to improve the situation, provide solutions and initiatives, and seek dialogue and negotiations. There are groups and activists who are aware of the seriousness of the situation in the camp and are both internally and externally seeking to break up and avoid any internal violent clashes, which could lead to the destruction of the camp and the displacement of the population, as seen in the Nahr Al-Bared camp. However, these initiatives alone are insufficient to create resilience among populations that are seen as potentially vulnerable. Instead of the reactions, programs, coordination and negotiation to tackle temporarily the situation, a general strategy should be developed for all actors, officials, institutions and organisations. It means, recognise the social roots of the problem, enables early interventions, promotes non-coercive solutions, and serves as an early warning system for emerging conflicts and grievances. By giving a role to mayors, teachers, religious leaders, youth workers, and even students, it reaches out to all sectors of society and defines the struggle against violent radicalisation as a collective task.

Mediation is a mechanism of action and intervention that has proven to be a working methodology for determining the different parties in conflict and the context of crises, particularly internal and external actors. However, in the EEH camp, we noticed that actors, detractors and opponents change and renew themselves. The stages of the conflict are characterised by changes in the pace and risks involved, their relationship to the past and their impact on the present.

How to transform such initiatives and develop them from an instantaneous intervention within the form of an intermediary to a strategy of sustainable intervention within the framework of mediation, along with the establishment of mediation as a culture and reference of conflict resolution and prevention?

It is clear from the field research in EEH camp that there is no balance in the initiatives for reconciliation, while limiting the relationship between the conflicting parties within the framework of security and legal institutions, Lebanese or Palestinian, and criminalised individuals or groups, such as Al-Shabab Al-Muslim, Bilal Bader, …. The role of the mediator is often played by a non-neutral party, either Lebanese or Palestinian, whether from security agencies or politicians.

These individuals and committees enjoy a legitimate social recognition for their work, both on the part of those relying on them, and other actors, which facilitate the establishment of mediators’ identity.

Through their work, intermediates in the camp are calling for ethical, not just judicial or social treatment. Their work could be developed as part of social development policies. In spite of their professional intervention in mediation techniques, they are able to re-create social and new accords at the neighbourhood level. This model can be built upon to form a healthy relationship between the local community in general and the Lebanese state or Palestinian political organisations. Hence, the success rate of mediation is higher so that it turns to a political-social tool. Mediation and its practice are turning to a tool of hybridisation between the Lebanese authorities and the Palestinian authorities, on the one hand, and the civil society, on the other hand. This work is grounded in the camp through the above-mentioned stakeholders through the establishment of “intermediate places” for social organisation, which includes both the public and private sectors, professionals and volunteers.

As for the intervention of the state in the process of mediation in EEH camp, it takes the form of interference from some politicians, as we have mentioned, from the region of Saida and some religious figures.

It is necessary to bring these key initiators to peaceful cooperation; they already have a key role to play in making peace a reality that cannot be violated; they can mediate even between leaders in the state. We need the help of those leaders. With the help of the second-tier leaders, local leaders from Saida, and the “first-tier ones”, the heads of parties and ministers in government, to open a national dialogue regarding the EEH camp and the Palestinian situation in Lebanon. Hence, similar to the Lebanese national dialogue, the same form of dialogue should be held at the Palestinian level among parties and officials in the camp along with Lebanese leaders involved.

The aforementioned are missing in the initiatives in EEH camp. The mechanisms of the solution remain local and reactive depending on the ability of the actors and their potentials. Conflicts are often resolved by a Palestinian or a local Lebanese intermediary, without calling for a summit among officials for resolving the root causes. Therefore, the problems of the process are not derived from “terrorists” themselves, but from the fact of ignoring the need of existence and agreement either by law or the policy of maintaining security.

Dialoghi Mediterranei, n. 51, settembre 2021

[*] Abstract

Questo testo cerca di studiare i fattori di spinta e di attrazione della radicalizzazione nei campi palestinesi in Libano. La radicalizzazione è intesa come un processo di escalation che porta alla violenza. Ci sono molti percorsi verso la radicalizzazione che non coinvolgono l’ideologia. Le tensioni nei campi profughi palestinesi sono esacerbate in particolare dalle continue pressioni causate dalle condizioni socio-economiche severamente mortificanti e dai diritti civili limitati loro concessi. Questo problema è stato amplificato dal conflitto siriano in corso che ha destinato l’afflusso di nuovi rifugiati palestinesi dalla Siria nei campi in Libano. Questo flusso, combinato con la preesistente carenza di alloggi, il sovraffollamento e gli alti tassi di povertà, hanno ulteriormente incrementato il rischio di tensioni e violenze armate. Così, alla luce delle dinamiche descritte di radicalizzazione e di conflitto armato violento, va letta l’iniziativa civile di deradicalizzazione intrapresa nel campo di Ein El-Helwe. Questo contributo si basa su una avvertita metodologia sociologica e su fonti primarie utili a comprendere alcuni meccanismi di radicalizzazione violenta e le strategie di contrasto intraprese ad opera di iniziative civili.

Note

[1] Maan News, “مخيم عين الحلوة .. 105آلاف لاجئ في كلم مربع”, “Ein El-Helwe.. 105000 laje’ in 1 km2”, February 5, 2015, http://maannews.net/Content.aspx?id=670895. (Last visit August 9, 2021).

[2] Aljazeera, “مخيم عين الحلوة عاصمة الشتات الفلسطيني الملتهبة”, “Moukayam Ein El-Helwe Asimat lchatatt lfalastine lmoltahiba”, Novenber 2, 2015, http://www.aljazeera.net/encyclopedia/citiesandregions/2015/11/2/ مخيم-عين-الحلوة-عاصمة-الشتات-الفلسطيني-الملتهبة. (Last visit August 9, 2021).

[3] It is a small Palestinian Salafist group based in the Taitbah neighborhood of the camp, led by Sheikh Ibrahim Dahsheh.

[4] Al-Akhbar newspaper, “Separation” wall around EEH camp: “As if we were in detention”, Amal Khalil, Monday, November 31, 2016.

[5] The concept of a ‘radical milieu’ has been introduced by Peter Waldmann and Stefan Malthaner in 2010. They were the first to argue that radicalisation is (also) ‘the result of political and social processes that involve a collectivity of people beyond the terrorist group itself and cannot be understood in isolation. Even if their violent campaign necessitates clandestine forms of operation, most terrorist groups remain connected to a radical milieu to recruit new members and because they depend on shelter and assistance given by this supportive milieu, without which they are unable to evade persecution and to carry out violent attacks [...] Sharing core elements of the terrorists’ perspective and political experiences, the radical milieu provides political and moral support’. Stefan Malthaner, The Radical Milieu, (Bielefeld: Institut für interdisziplinäre Konflikt- und Gewaltforschung (IKG), November 2010): 1; see also Stefan Malthaner and Peter Waldmann (Eds.), Radikale Milieus. Das soziale Umfeld terroristischer Gruppen (Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag, 2012).

[6] A battle between the Lebanese army and Fatah Al-Islam led to the destruction of most of the camp during the bombing of the Lebanese army, which also suffered heavy casualties from May 2007 to September 2007. Shaker Al-Absi, leader of the Salafi Jihadist group, Fatah Al-Islam, brought together Palestinian, Lebanese and Arab fighters. Nahr Al-Bared was destroyed and the 30,000 people who lived there, were deported.

[7] Annahar, ‘Likaa loubnani falastini fi Darat Majdilyoun wa wathikat tada’iyet ahdath Ein El-Helwe’, August 26, 2017, https://www.annahar.com/article/648686- لقاء-لبناني-فلسطيني-في-دارة-مجدليون-ووثيقة-تنهي-تداعيات-احداث-عين-الحلوة (Last visit August 9, 2021).

[8] Saleh, M. “Ghorfat amaliyat lilfasail alfalastiniya li moutaba’at atatawourat wa kafat atahadiyat”, “غرفة عمليات للفصائل الفلسطينية لمتابعة التطورات وكافة التحديات”, Alitijah, August 28, 2017.

[9] He preferred to be anonymous.

[10] Interview with Major General Subhi Abu Arab, Commander of the Palestinian National Security in Lebanon, Saida, 15-11-2017.

[11] Interview, Sheikh Maher Hamoud, Saida, 13-11-2017.

[12] Army interview, Saida, 13-12-2017.

[13] The Muslim youth, Al-Shabab Al-Muslim is a Salafist jihadist group in the EEH refugee camp, which regularly engages in regular military skirmishes with the Fatah.

[14] Dead in January 2020.

[15] Interview, EEH camp, 11-10-2017.

[16] Raed Abdo, interview, EEH camp, 10-11-2017.

[17] Annahar, ‘Annahar hasalat ala video I’tikal ajaych li amir Daesh Imad Yasin fi moukhayam Ein El-Helwe’, November 15, 2016, – النهار-حصلت-على-فيديو-عملية-اعتقال-الجيش-الجيش-لامير-داعش-عماد-ياسين-في-مخيم-عين.

[18] Interview with young Muslim leaders in EEH camp, 29 April 2017.

[19] Asemat alshatat, “Bilal Badr Alana moughadarat moukhayam Ein El-Helwe”, January 2, 2018,

[20] Interview with leaders of Muslim youth, Ein El-Hilweh camp, April 29, 2017.

[21] Asemat alshatat, ‘Ein El-Helwe nahwa tay safhat al-ichtibak al-akhir’, February 26, 2018, 26 February 2018.

[22] On February 21, 2017, Mounir Al-Maqdah stated that «all the issues that were discussed with General Munzer Hamza and the commander of the Palestinian national security in the Saida region, Brig. Gen. Abu Ashraf Al-Armushi and the commander of the joint force, Colonel Bassam Al-Saad, have been overcome in a meeting held at the Embassy of the State of Palestine in Lebanon under the auspices of the supervisor charged with the Palestinian refugees case in Lebanon, Azzam Al Ahmad».

[23] Palestinian News Network, “Hal infaratat allijna alamnia alfalastiniya aloulya wa batat almoukhayamat fi mahab atawator ?”. February 14, 2017, http://www.pn-news.net/news.php?extend.4929.3 (Last visit August 9, 2021).

[24] Interview, EEH, 15-11-2017.

[25] Maj. Gen. “Ibrahim Ibrahim discussed the file of wanted men in Ein el-Helweh with a delegation of Palestinian factions”, 27 October 2017. http://aliwaa.com.lb/أخبار-لبنان/سياسة/اللواء-ابراهيم-بحث-ملف-المطلوبين-في-عين-الحلوة-مع-وفد-من-الفصائل-الفلسطينية/ (Last visit August 9, 2021).

[26]Asemat alshatat, “Masadr ijraat ajaych alloubnani ind madkhal moukhayam Ein El-Helwe kad touadi ila radat fi’il wa risala ila kiyadat ajaych”, January 4, 2018.Asemat alshatat, “ajaych youkfol Tarik alnabaa fi moukhayam Ein El-Helwe”, January 2, 2018.

[27] Sheikh Maher Hamoud is the president of the World Union of Resistance Scholars. He was a founder of the Islamic Group in Saida in 1971 and took charge of it until 1979. He was one of the founders of the Muslim Scholars Association in 1982 and the Islamic Front in Saida from 1985 to 1990. Before becoming the Imam of Jerusalem mosque, an independent mosque (not following the religious authorities of Dar Al-Ifta), he was the Imam of the Grand Mosque in Saida between 1979 and 1980. He is still the first negotiator between Palestinian and Lebanese authorities and intervene in any clashes to maintain security.

[28] MP Ousama Saad is the leader of the Nasserite Popular Organization and a former MP. He was never on good terms with the Future Movement because of its economic policies. He is close to the Palestinian circles and demanded always a radical solution by adopting a comprehensive national, political and social approach to the EEH camp. He played the role of “mediator” between the camp factions, the Palestinian forces and the Lebanese neighbourhood. Due to his presence on the ground, he is one of the few politicians to visit the camp and communicate with the Palestinian organisations. After the reduction of UNRWA services, he met with several Palestinian delegations from PLO, the coalition and the Islamist forces to deal with any possible violent reactions.

[29] MP Bahia Hariri from the Future Movement has been in charge for decades with the file of Palestinian refugees. As a deputy from the city of Saida since 1992, she has emerged as the most important local “mediator” between the camp authorities and the Lebanese government. On several occasions, Hariri mediated in internal conflicts between warring factions in the camp and succeeded in resolving conflicts in volatile situations, most recently during the battle with Bilal Badr in August 2017. Bahia Hariri intervenes sometimes financially to resolve conflicts. Once she admitted paying an estimated 100,000 USD to Jund Al Sham fighters as compensations for leaving their homes in Al-Taamir quarter, since Fatah was unable to pay such compensations. Most of those fighters went to Nahr Al Bared camp. Hariri is considered a reference for resolving conflicts in the camp by Lebanese and Palestinian circles.

[30] Almustaqbal, “ Tazahoura fi moukhayam Ein El-Helwe “taradat” al-mousalahin: jarihan fi ichtibak bayn “Fatah” wa “Jund acham””, January 24, 2005.

[31] He is also a political leader in Hizb ut-Tahrir, a political bloc whose principle is Islam and seeks to restore the caliphate.

[32] Interview, EEH, 10-11-2017.

[33] Pn-news, “Nas almouzakara alati kadamatha almoubadara acha’biya fi moukhayam Ein El-Helwe li moudir ‘am wikalat lunrwa fi loubnan”, December 20, 2016, http://www.pn-news.net/news.php?extend.4293.3. (Last visit August 9, 2021).

[34] Interview with Faiza Khatib, Saida, 14-12-2017.

Bibliography

Bonelli, L. and Carrié, Fabien. La Fabrique de la Radicalité, Une Sociologie des Jeunes Djihadistes Français, Paris, Seuil. 2018.

Borum, R. ‘Understanding the terrorist mindset’, FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, 72 (7), July 2003: 7-10.

Dorai, M.k. Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon, The Geography of Exile, Publications of the French National Center for Scientific Research: Paris. 2006.

Dot-Pouillard, N. Between Radicalisation and Mediation Processes: a Political Mapping of Palestinian Refugee Camps in Lebanon, Lebanon Support. 2015.

Hanafi, S. and Knudsen, Are. Palestinian Refugees: Identity, Space and Place in the Levant. Routledge. 2010

Institute for Strategic Dialogue, Policy Briefing, Tackling Extremism: De-radicalisation and Disengagement (Copenhagen ISD, 2012) ; available online at: http://www.strategicdialogue.org/allnewmats/DeRadPaper2012.pdf.

Kortam, M. « Usbat al-Ansar al-Islamiya. De la radicalisation à une dé-radicalisation inachevée », in Dialoghi Mediterranei.

https://www.istitutoeuroarabo.it/DM/usbat-al-ansar-al-islamiya-de-la-radicalisation-a-une-de-radicalisation-inachevee/. Mai 2021.

Kortam, M. Nicolas Dot-Pouillard, “A Future Without Hope? Palestinian Youth in Lebanon Between Marginalization, Exploitation and Radicalization” <https://www.daleel madani.org/sites/default/files/Resources/a_future_without_hope_palestinian_youth_in_lebanon_between_

marginalisation_exploitation_and_radicalization.pdf>, Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA), Beirut, November 2017.

Kortam, M. Jeunes palestiniens, jeunes français : quels points communs face à la violence et à l’oppression (Palestinian youth, French youth: common points face of violence and oppression). Paris, L’Harmattan. 2013.

Mc Cauley, C. and Sophia Moskalenko, Friction. How Radicalisation Happens to Them and Us, (Oxford: University Press, 2011): 206-214.

Moghadam, F.M. “De-radicalisation and the Staircase from Terrorism”, in David Canter (Ed.), The Faces of Terrorism: Multidisciplinary Perspective (New York: John Wiley, 2009): 278-79.

Putnam, R.D. , Bowling Alone. The Collapse and Revival of American Community, New York, Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Marra, R, F. Islamic movements and forces in Palestinian society in Lebanon: Genesis, Objectives, tasks, Zaytouna Center: Beirut. 2010.

Schmid, A.P. ‘Glossary and Abbreviations of Terms and Concepts Relating to Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism’; in A.P. Schmid, 2011.

UNRWA, “Ein El-Helwa camp”, https://www.unrwa.org/ar/where-we-work/ لبنان/مخيم-عين-الحلوة-للاجئين.

UNRWA, “Protection Brief: Palestine Refugees Living in Lebanon”, UNRWA, May 2016

UNRWA, European Union, “Employment of Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon, Overview”, May 2016.

______________________________________________________________

Marie Kortam, docente di sociologia all’Università di Beirut, presso il dipartimento di Storia contemporanea, ha conseguito il dottorato di ricerca all’università di Parigi. Membro del Consiglio arabo per le scienze sociali, collabora a numerosi progetti di ricerca sulle relazioni civili-militari. Ta i suoi interessi scientifici: la violenza e i movimenti sociali, i processi di radicalizzazione politica e l’organizzazione dei gruppi islamisti. Tra le sue ultime pubblicazioni si segnalano: Fighting terrorism and radicalisation in Europe’s neighbourhood: Discours Sur la Violence (Univ. Europeenne, 2018); How to scale up EU efforts; Jeunes du Centre, Jeunes de la Peripherie (2018).

______________________________________________________________